Rubber Market Macro-Analysis: August 2021

A Response to “The Rubber ‘Apocalypse’”

As ripple-effects from the initial COVID-19 outbreak reverberate, both domestic and foreign economies have begun to bear the brunt of the negatives that the outbreak initially triggered. In the U.S., there have been a number of supply chain disruptions that have caused massive price increases and dwindling supply—beef, lumber, and semi-conductors are just a few of the industries that have dealt with such volatility, only to proximally return to equilibrium levels. With that said, there is one commodity going through the beginnings of a similar cycle that - because of its industrial uses, trade, volume, and political implications - is worth examining under a microscope.

In July of 2021, CNBC released a video titled, “What The Rubber ‘Apocalypse’ Means For The U.S. Economy”, in which the network enlists a number of academics to outline the growing problem of rubber demand outpacing rubber supply, especially as production projections look grim.

“We are using tires more and more,” Stefano Savi, director of the Global Platform for Sustainable Natural Rubber, told CNBC. “The amount of mileage that we’re going to do as a global population is definitely bound to increase, and that’s why the demand for rubber is really continuing to increase.” Rubber, first and foremost, is a product of the natural world that has achieved widespread ubiquity with consumer and industrial products since its uses became widespread during the industrial revolution. Though there are some viable rubber substitutes, such as composite or dandelion-derived materials, none have been viable enough to replace natural rubber in its applications. Between exogenous shocks from COVID and climate change, along with persistent demand spikes, the rubber industry is being stretched thin. While there have not been massive price hikes for rubber yet, the industry is seeing a large number of growers exit as it is too expensive to produce relative to other goods like palm oil. With this, the overall cost index of industrial inputs is rising rapidly (+60% YoY), of which rubber is a major part. I believe we are seeing the early signs of the rubber industry going ‘apocalyptic’, in the same direction as commodities like beef or lumber, but with more wide-spread implications.

Similar to commodities like oil and lumber, the outbreak of COVID-19 heavily impacted the rubber industry, with global production decreasing by 5% from 2019 to 27.4 million metric tons. Noting these disruptions, the global synthetic rubber market size is estimated to be 19.1 billion U.S. dollars in 2021, with demand projected to expand nearly 1.1% annually to 2023 in the United States. CNBC cites that the global natural rubber market was valued at nearly $40 billion in 2020, and demand for rubber is expected to increase. One analysis predicts the natural rubber market could be worth nearly $68.5 billion by 2026. Increased demand in things like car tires and latex gloves, coupled with climate change and supply chain disruptions, have created concerns in the rubber industry. Katrina Cornish, Ph.D., a professor at Ohio State University and a global expert on alternate rubber and latex production, said the problem could become more prevalent in the near future. “We could be on the cusp of a rubber apocalypse,” Cornish told CNBC. “COVID doubled the demand for [latex] gloves from 300 billion to 600 billion.”

The total annual supply of natural rubber of ~20 million metric tons is almost entirely produced by small-plot growers working tiny plots of land in tropical forests; however, this fragile supply is under threat. The rubber tree Hevea Brasiliensis is no longer grown commercially in certain parts of its native habitat due to the prevalence of South American leaf blight, a catastrophic pathogen which killed off Brazil’s rubber industry in the 1930s. The BBC reports how, “strict quarantine controls have kept the disease contained to South America for now, but arrival in Asia is thought to be almost inevitable… Farmers elsewhere in the world still face local pathogens such as white root disease and other leaf blights that have made the leap from neighboring oil palm plantations.” Climate change is another factor that cannot be ignored when looking at rubber production; in particular, Thailand's rubber production has been hindered by droughts and floods spreading disease-causing microbes across usable land.

The troubles plaguing the rubber trade can be broken down into two distinct causes, each coalescing to create a unique economic storm. First, there is an exogenous “supply shock” underway. From Eleanor Warren-Thomas, a research fellow at Bangor University who has studied the dynamics of rubber plantations, "Oil palm and natural rubber make the same money per unit of land, but the labor input is higher for rubber," she says. "Because the rubber price is falling, farmers are switching from producing rubber to selling the timber for near term profit, and growing oil palm instead." This trend is occurring simultaneously with the continued threat of blight and climate disruptions, and it shows how firms are willing to transition into another industry when the fixed cost is simply too high to operate. “A growing demand for rubber and short supply should be good news for the farmers, as it would make rubber more profitable to grow. Unfortunately, that's not the case. The price of rubber is set by the distant Shanghai Futures Exchange, where brokers speculate on value.” Robert Meyer, CEO of rubber conglomerate Halcyon Agri, said. “The pricing has nothing to do with the cost of production. [The] price of rubber per metric ton can vary three-fold from one month to the next, and in recent years has been held at very low values. The mathematics smallholders make is that income equals price times volume.”

If the price of rubber (as an input) increases, the supply curve will shift left as sellers are less willing or able to sell goods at any given price. This trend defines the rubber market, but also the market for any good, manufactured or otherwise, that depends on rubber as an intermediate (the case can be made that this input would affect the world economy as a whole). From the context of the United States, knowing that rubber has to be imported, another source of shock is the cost of imported goods that are used as inputs for domestically-produced products. In these cases, the lesson is that higher prices for inputs cause SRAS to shift back to the left. This shock is predicted to continue and worsen into the future, as climate change and rapid industrialization pull on both ends of the rubber supply network. Again from Robert Meyer: “Since 2010, global consumption has risen from 10 million metric tons to 14 million metric tons today. We are using more and more rubber, while its supply becomes less and less sustainable. Simply put, natural rubber is an industry headed for crisis.”

These supply shocks, in tandem with a volatile rubber futures market (the 8/17/20 – 8/17/21 Range is $163.5 – $338 per 5000 kg contract), has led to huge price volatility in the price of natural rubber. Since 2000, natural rubber prices have hit an all-time low of circa $500/ton, followed by an all-time high of circa $6000/ton in 2011, before hitting a recent low in 2016 at $1000/ton. Another report from Halcyon outlined how the supply side of natural rubber is reliant on an uncoordinated network of millions of individual smallholders reacting to pricing signals. At high prices, growers plant rubber trees. It takes four to seven years to yield, by which time prices are likely to have fallen – and historically, they have (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1

With prices falling (down over 50% from 2010), the most prudent approach would be to scale back supply – which a small-scale subsistence farmer cannot do as their income is determined by P * V (price x volume). Low prices drive growers to over-tap their trees to extract more rubber, weakening the plants and making them more susceptible to blight. The low prices have also discouraged planting of new trees to replace those at the end of their commercial lifespan, requiring a 5-7 year wait for maturity. Because of this, as previously mentioned, many farmers have abandoned plantations entirely.

Looking at the context of the United States, this rubber shock creates exogenous changes in the demand for goods & services. This shift in the supply curve changes in both consumption (not buying more expensive goods that are dependent on rubber) and household wealth (if goods are more expensive, people are incentivized to save). This could also lead to changes in consumer confidence, as dents in the supply chain tend to have large repercussions in how consumers view the market as a whole. Bloomberg recently reported that consumer sentiment in the U.S. has dropped to its lowest level since 2011. A result of the decline in consumer confidence is that the exchange rate falls, and the trade balance increases; this will result in a greater portion of consumption being from foreign goods, rather than domestic, in the short run. However, with rubber being a global commodity, domestic consumers might not be able to escape higher prices by simply looking abroad.

Secondly, there is rising rubber prices. Though this could be a symptom of the aforementioned supply shock, the increased demand in rubber is also a culprit and that is the lens in which this externality will be assessed. The BBC reported that, while rubber demand tanked during the early half of the COVID pandemic, “demand outpaced even the most bullish predictions” as lockdown restrictions began to be lifted. "Demand has since eclipsed supply," says Meyer of Halcyon again. "Now there is an acute shortage [of rubber] in destinations, and inventory held by [tire] makers is very low." To forecast, the global natural rubber industry keeps increasing at an annual growth rate of ~2-3%; because of this, experts tend to believe the industry is over capacity. With rubber being an input in so many applications, this would increase prices across consumer goods, since the price of manufacturing, maintenance, shipping, and all else would rise. If this seems like an overreach, remember that any good you have ever purchased in a store that was not made on site was dependent on rubber for it to get to the shelf. While the price of rubber has not sky-rocketed, we are already beginning to see the impact COVID had on industrial inputs as a whole:

Figure 2

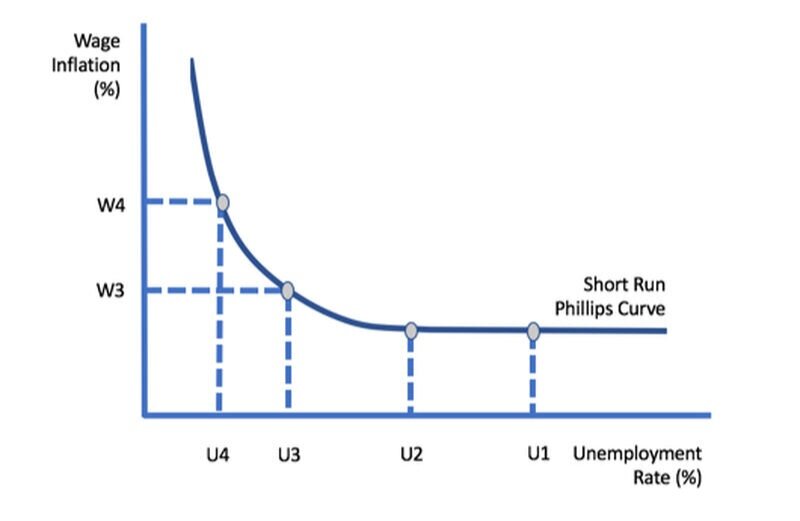

Even though the 10-year price is up by only 0.4%, there has been a huge price jump in the past five years, from when rubber prices were at a ten-year low. In fact, just in the past year, the commodity industrial inputs price index jumped by 61.70%. Both the opposing forces of dwindling supply and increasing demand can lead to an increase in prices, and since they are occurring in sync, we can expect the overall price level of rubber to increase in the short run. When rubber becomes more expensive, the implications are more far and wide than other commodities (rubber is an essential component in manufacturing, agriculture, trade, transportation). Without a substitute, a short run increase in the price of rubber would increase the prices for most consumer goods, and would also lead to the continued increase in the price of the industrial inputs index. Since rubber is such a commodity, a global increase in the overall price level for most goods would lead to upward inflationary pressure, especially as manufacturing and shipping become more expensive. Rubber’s global ubiquity would save an individual nation or currency from depreciating compared to its economic counterparts; however, if growers in producing nations are not able to seamlessly transition into palm oil or other commodities, those nations would indeed be hit the hardest by this uptick in global price level. If this inflation is unexpected, it would massively hurt creditors around the world since most loans are specified in nominal terms. Also, as inflation increases in the short run, the validity of information on market prices and economic outlooks would reduce drastically as firms either do not adjust fast enough, or are not willing to undertake menu costs. Over the years, this unexpected inflation would impact employment, investment, and firm profits. In fact, unemployment maintains an inverse relationship with inflation as represented by the Phillips curve (below Figure 3):

Figure 3

Typically, as unemployment increases, consumers purchase less goods, thus causing downward inflationary pressure. But inflation is the dependent variable in the Phillips curve—and with an exogenous price shock, as with the looming rubber apocalypse, the uncertainty of inflation leads to lower investment and lower economic growth, thus leading to an increase in unemployment. If the exogenous shocks to the rubber supply are mitigated in the short run, then an increase in unemployment could actually provide the necessary downward pressure needed to bring the world economy back to equilibrium. However, since the problem is dual-wielded, there does not seem to be any reason to think the increase in rubber prices would end in the short run outside of an increase in technological progress. Where “What The Rubber ‘Apocalypse’ Means For The U.S. Economy” described a more broad problem developing on the horizon, there are immediate, real-world economic implications for both the rubber market and the global economy as a whole. To summarize, the increased demand and endangered supply of the Hevea Brasiliensis has led to demand actually outpacing supply, an increase in price level, a decline in consumer confidence, and also has led to firms exiting the industry entirely—further straining the already-slim numbers of growers.